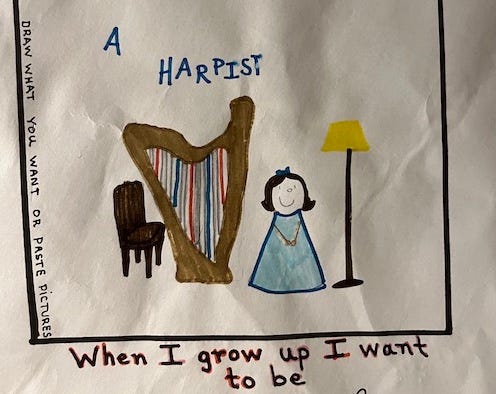

I started this newsletter to share more transparently about my experiences as a classical musician/academic trying to make a living and a career in the 21st century, with the addendum that I'm not satisfied with the way things are. Surely, the little worm in my brain constantly muses, we can re-think this situation. Over the next two installments, I thought I'd explore how the feeling of wanting to quit is sometimes not about failure. In the case of my story, that feeling was a strong symptom of wanting to be more than one's profession.

There used to be only four links in my web browser's Favorites folder: Gmail, Outlook, DropBox, and Keguro Macharia's 2018 essay for The New Inquiry, “On Quitting.”

“On Quitting” is a psychoanalytical fever dream, a young academic's cry for help in a world that thrives on breaking the spirits of its most spirited people. It's a story of realizing that there are places in the world where you can feel more than just constantly run down by the career machine, where who you are (in Macharia's case, a Black person), isn't a statistic that can be used for an administrative agenda. It's a prognostic call for care as an underlining social principle—and not in the capitalist sense of happy people = happy, more productive workers—but in the sense of living an ethical life for yourself and creating one for others.

When Macharia's essay was published, I had just started year 3 of my DMA, year 2 of a very unfulfilling adjunct teaching situation (which I've written about here), and year 1 of a long-distance relationship. It's fair to say that life felt very uncertain in September 2018. So, during that year, I thought a lot about quitting.

In 2019, I made the difficult decision to give up my two adjunct jobs and a growing private studio in South Bend to move to Ontario to be with my partner. In August, we got married. In September, I was unemployed and living in a new country where I had no professional connections and no friends. Each day passed by excruciatingly slowly. I spent a lot of time sitting doing a lot of Sudoku, binge-listening to a hilarious (unfortunately now-defunct) podcast about terrible romance novel writing (“She slid bonelessly to the floor”), and staring at my computer screen, wondering how to tackle the weird and challenging dissertation topic into which I had thrown myself.

During a dinner with the then-dean of the music school where my husband worked, her husband turned to me at one point and said, “I followed my spouse so she could follow her dreams. I know what it's like to move to a new place where you're a nobody.” That hit different. My inner raging feminist wasn't happy about the prospect of being known around town as “Patrick's wife” and wondered if that would be my fate if I pursued music work in our city. So, during that year, I re-read “On Quitting” and thought a lot about quitting.

In 2020, the pandemic hit. Every musician thought about quitting. I finished my DMA and—while unshowered, in pajamas, and working on a Sudoku—unceremoniously watched the virtual commencement on our little TV. By September 2020, I was fortunate to have been hired as the sessional harp instructor at the university, but by that time, my husband's full-time contract hadn't been renewed, and he started teaching as an adjunct. We were stressed about finances (one of my tasks was budgeting $60/week on groceries for two people), and I took on extra work as an English tutor. Out of all the grants, competitions, and festivals I applied for, only two slightly significant projects worked out: a small grant to work on my transcription of Leo Brouwer's The Black Decameron and the publication of my first peer-reviewed article (so, not much). During 2020 and 2021, my husband and I talked often about quitting.

In 2022, I turned 28, which is an important age in classical music circles because that's the age limit for a lot of competitions (for some, it's 32). At the end of 2021, I had decided to apply to a big international harp competition—my last hurrah—and told myself that if I did worse than the last time I participated in that competition, I'd legitimately start exploring work options in other fields and possibly even going back to school. Around the same time, I had applied for the harp/entrepreneurship job at Florida State University, uncertain whether my application would get a second look since I didn't exactly come off as an “entrepreneurial” musician, i.e., hadn't started a non-profit, festival, or chamber ensemble like many of my colleagues had done. I had also applied for two grants from the Ontario Arts Council, one of which was for a multidisciplinary performance project that was totally out of my comfort zone. And, I applied for a much smaller competition in Chicago as a practice run for the big competition.

To make a long story short, on the same day I found out I had received both council grants, the results for the smaller competition came back, and I was disappointed. I had hoped this competition would affirm aspects of my playing I had been really trying to improve for a few years, and the fact that one of the judges ranked me behind a number of younger players who were technically solid but perhaps less musically sophisticated made me wonder, Maybe I'm getting too old for this. I left Chicago early the next morning, driving with a broken wheel bearing through a scary snowstorm, and thought again about quitting—even as I was also getting ready for my interview at FSU in two weeks.

One thing that was different about my inner monologue this time was that quitting was less about leaving the harp altogether. Rather, it was about leaving a certain mindset about the harp; namely, that I was a harpist preparing for harp competitions with a very specific value system in place, and that everything I did in my professional life was informed by my training and experiences as a harpist. Could I quit being a harpist without quitting the harp? Could I be a philosopher and a teacher who plays the harp, or a woman who is learning to inhabit her womanhood, with the harp just being part of that journey?

I like to think that this realization—along with putting in the work to address some performance anxiety, which I'll write about some other time—was extremely pivotal to how I decided to approach both my FSU interview and the other competition (I still pinch myself because I still can't believe it was possible for both those opportunities to work out).

For some of you, the idea of being a well-regulated individual may seem self-explanatory. However, both academia and music encourage an extremely myopic lifestyle. Most musicians have spent an inordinate percentage of their lives perfecting their skills. You’re told to pour heart, soul, and anywhere between 4 and 8 hours of practicing in your instrument because it's your passion, and something you're passionate about should consume every waking minute of your life. If it doesn't, that means it's not actually your passion. Likewise, in academia, the very structure of the job is to encourage living and breathing your work—ideally, because you're passionate about teaching, or about research, or about improving society through higher education.

As a workaholic married to another workaholic, I really abhor this mentality. Not only is it exploitative and manipulative of knowledge workers—by distracting us from unsustainable labor conditions grounded in the ideology of passion—it reduces our ability to see both the world and ourselves outside the perspective we naturally inhabit, which usually entails a whole slew of damaging biases and behaviors that we've internalized as normal.

So, for the next installment, I'll discuss two fundamental questions that I ask my entrepreneurship students at the beginning of the semester:

What drives you? (passion, ambition)

What feeds you? (nourishment, care)

What's most interesting is when the answers to the two questions are wildly different, even contradictory. Certainly, they are for me, and I think that tension is the reason I've considered quitting. Perhaps the solution isn't to wander through life until you find a passion that is nourishing, but to think about how to re-structure the way we work and think about our work so there is enough space and time to nourish ourselves. How does a musician (and/or academic) learn how to be more of a whole—cared for, not complete—person? Moreover, how are our industries and institutions failing to provide the freedom to do so? How can we circumvent that?

Until next time.

Hugs and kisses,

Noël

My new recommendations corner, which I'm going to call “The Corner of Wondrous and Powerful” (in reference to my all-time favorite public art piece in Brattleboro, VT). Private Property - KEEP OUT, indeed.

Listening: Caterina Barbieri's Ecstatic Computation. Highly recommend listening to this alone in a totally dark room.

Watching: Mark Lewis’s delightfully wry 1988 documentary on cane toads. I watched it over the holidays and recently re-watched it because it's. that. good.

Reading: Joanna Russ’s 1970 sci-fi novel The Female Man. There's a section when the character Janet (from Whileaway, a prototypical feminist utopia planet) is cornered by a creepy old dude at a party, and he proceeds to mansplain to her why women need men to help/protect them. Of course, Janet is enraged. However, she is silent the entire time because the narrator has been physically restraining her (to avoid an violent public altercation):

Our struggle must have imparted an unusual intensity to her expression because he seemed extraordinarily flattered by what he saw […] “You're a good conversationalist,” he said.

I laughed out loud.