ai-ya! 哎呀!

I'm an artist and an academic. Here's why I'm not afraid of AI.

Last week, I wrote my first ever AI policy for assignments in my entrepreneurship course syllabus, after reading this excellent article in The Atlantic. In the music and social theory course I'm co-teaching with my musicology colleague Erol, we've been talking about using the course to launch meta-discussions about critical thinking with the students. The reality is that generative AI has become ubiquitous as a lifestyle tool, and there's no going back anymore. For every new-fangled AI-based service getting released into the word (ahem, Microsoft Copilot Podcasts), we need one more conversation about how it affects the whole gamut of human life and how we want to engage with it.

In this current AI-riddled zeitgeist, then, it seems more important than ever for humans to consider how technology has affected our cognitive development, our cultural preferences, our social relationships, and even our daily physical movements. “Biopolitics” is no longer just about an 1984-esque, political institutional thing. Sure, we're still being monitored by corporations and governments at an incredibly scary level, but we're all more OK with that than we maybe would admit—so much so that we've started self-monitoring to generate even more data (yup, looking at everyone who uses any form of smart biometric tracking device for personal/recreational purposes).

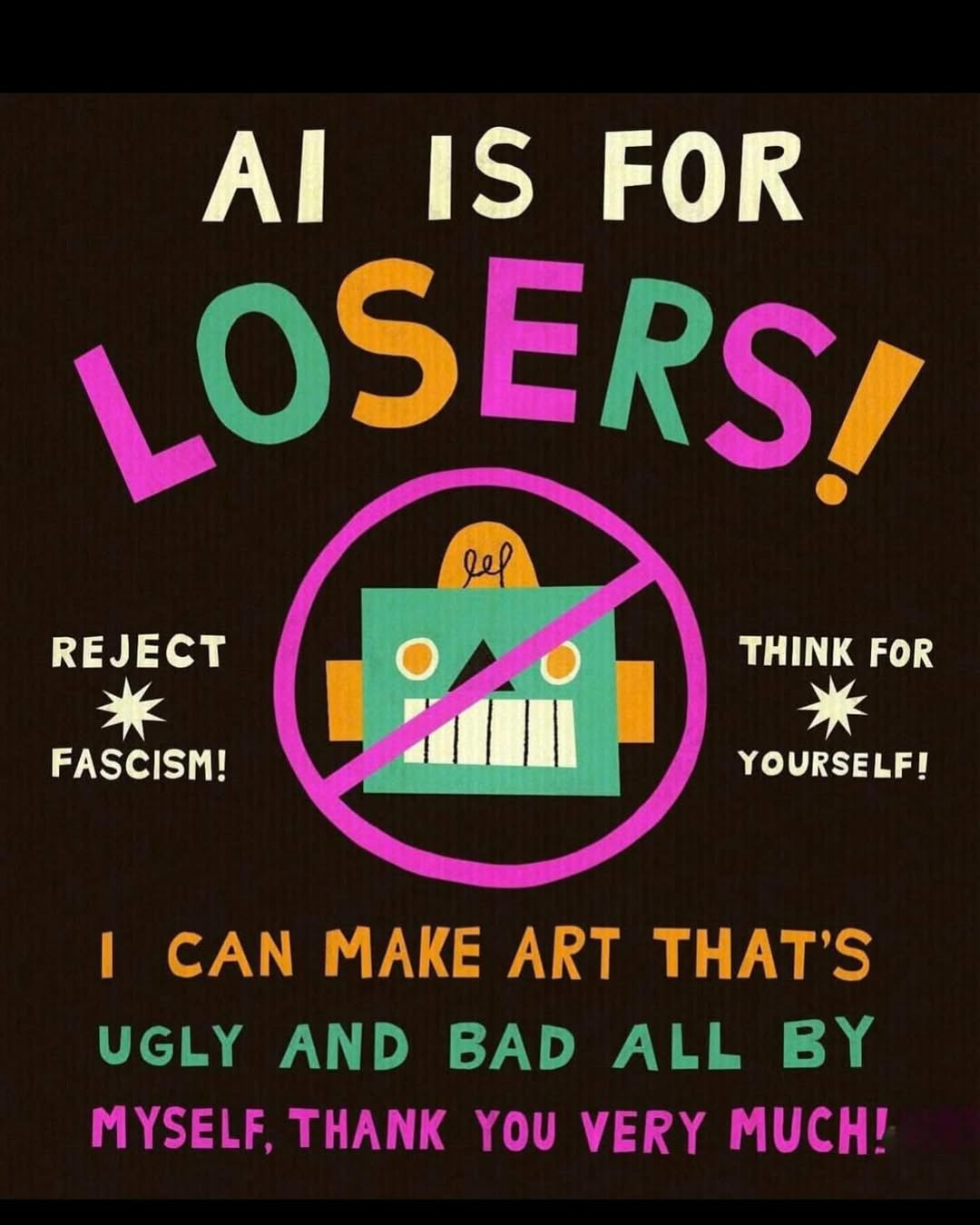

Sure, one can argue that mass media and the internet and personal devices fucked us up, and that the only antidote is to become a Luddite or hermit. If either lifestyle is too extreme for you, the second best option seems to be posting ridiculous paeans about the value of human art on social media, such as this one:

A few days ago, I saw a Minnesota Orchestra marketing graphic emblazoned with the phrase “I (heart) AI,” following by smaller text revealing that “A” stood for “A magical night spent seeing some of the world's finest” followed by “I” for “instrumentalists.” The joke is, of course, that human musicians can and should not be replaced by AI, though part of me also wonders whether the marketing team at the orchestra did this because they know that a) anything invoking “AI” is buzzy and b) social media will push content that is controversial in any way.

The problem I have with humanists is that—and I am painting in broad strokes because this is Substack—there is a naïve insistence that human nature is inherently good, that we want to do good things and create civil, productive societies, and that the human mind is this superior phenomenon that is endlessly generative of brilliant knowledge and art. As an artist, I feel the stakes strongly, and as a music educator, I worry about the future of work for my students. In my teacher role, though, I feel pretty strongly that, in addition to improving my students’ disciplinary skills and knowledge, it's also my responsibility to teach them how to face the world, whether that means teaching professional behavior, giving appropriate life advice, or showing them different ways they can engage with society as musicians AND as human beings.

Without being a AI apologist, we shouldn't scapegoat ChatGPT when the emergent social and economic problems are really symptoms of human shittiness. A few affecting those of us in the arts and culture sector:

corporate greed using AI to raise profits, at the expense of workers (including cultural workers like musicians)

citizens of rich countries’ insatiable appetites for more experiences, more content, more everything, creating a host of other problems (fragile tourism-dependent economies, incredible amounts of e- and actual waste, environmental issues related to resource extraction)

artists getting injured and overworked, whether it's because they have to performing a lot to make a living wage, their agents are overbooking them to make more money, or the cultural expectation is to perform all the time

academics chasing higher acclaim and salary by boosting their research, sacrificing any sort of commitment to innovative, sustainable, and thoughtful pedagogy (ideas and practices change - you absolutely cannot teach the same way or the same material for even 5 years)

in music academia, I see the fallout from issues such as university administrators hiring adjuncts who are superstars or musicians with industry experience (many of whom have limited teaching background and little pedagogical versatility) AT THE SAME TIME telling faculty to admit more and more students who have moderate to severe gaps in communication, writing, and even performing skills

AI cannot really fix these problems in any meaningful way, at least not in ways that will create healthier social and economic systems (unless AI can eliminate human greed and selfishness). If anything, AI tools, especially ones marketed as saving time or money, tend to amplify greed and selfishness. So, these technologies—especially when used by humans—are kind of like a fun house mirror for human thought and behavior (not unlike the way Jack Halberstam theorizes the monster in Skin Shows!). They show us in our most unflattering angles, the existing vulnerabilities in our social, economic, and political systems ready to be exploited by the bad actors rife in the world.

A few years ago, I wrote a silly, indulgent article for my friends at The Collective about ChatGPT, back when the world first went insane over the possibility that creepy AI chatbots could take over human interactions and tasks. Even in the nascence of public conversation about AI, I felt increasingly frustrated by the emphases on what AI could and couldn't do, which was really based on a Battlestar Galactica-esque pitting of machine against human—itself based on a selfish anxiety about human extinction (which itself has been the way humans have justified shitting over the planet and everything on it).

I currently feel no compulsion to joining the academics and artists around the world who are scrambling to figure out the hottest new way they can incorporate AI into their work. Why? It's not because I am a crusty classical musician pining for times yore and disinterested in any form of new technology. On the contrary, I enjoy thinking about the philosophical implications of machine intelligence and human-machine relationships beyond the “us vs. them” narrative. To me, AI is just another technology—like all the other major ones that preceded it—that comes with as many dangers as it does benefits. It feels significant because it has dramatically upended the way we relate to things and live in the world, but that just means there is a whole new pile of challenges to sift through, new problems to solve, and new theories to imagine!

If we are failing to think critically, it is not just because of generative AI, social media, or smartphones have caused us to become stupid. We have failed to intervene on the structural conditions that lead us to seek (or create) technological band-aids in the first place. For example, a long-term solution to Patrick's never ending admin to-do list is not an AI-powered assistant that organizes his whole day for him. It boils down to why he has to work three jobs as a musician (the extremely competitive and tenuous economic ecosystem for artists in Canada); why his university wants him to open the enrollment floodgates for his choir (up to 150 students); or why community choirs have turned into vehicles for regional career building, making new work commissioning, marketing, ticket sales, and grant writing necessities that those organizations aren't equipped to support.

Because it is 11 PM on a Sunday, and I still have to prepare 100+ pages of readings for my class this week, I will end with this:

As an artist, I am not afraid of AI because I recognize the limits of its utility, and I recognize the limits of an existence in a world defined by utility. Tools aren't bad things—indeed, they help us get things done. When we turn ourselves into tools that create commodities for quick profit and easy consumption, we may very well lose to machines. So, think actively about what cannot be replicated by an algorithm: for me, it's not genius or creativity or humor or intelligence, but the expansive intangibility, the visceral tangibility, and the urgent relationality of being life.

Until next time,

Noël 🎄

The Corner of Wondrous & Powerful

👂🏼 I asked Patrick to recommend a Renaissance composer whose works I can listen to for a whole month, since a) I am trying to see whether the musical equivalent of oatmeal will drastically change my musical sensibilities and b) I'm interested in learning more about sacred Renaissance polyphony as we continue working on The Mother's Teeth projects. So, I guess I am listening exclusively to Tomás Luis de Victoria (and Ethel Cain) until the end of September.

📖 More from The Atlantic on AI, but this time an excoriation of its effects on how people develop le bon gout in an era of consumer-driven taste: “Good Taste is More Important Than Ever.”

Like any skill, taste can be developed. The first step is exposure. You have to see, hear, and feel a wide range of options to understand what excellence looks like. Read great literature. Listen to great speeches. Visit great buildings. Eat great food. Pay attention to the details: the pacing of a paragraph, the curve of a chair, the color grading of a film. Taste starts with noticing.

The second step is curation. You have to begin to discriminate. What do you admire? What do you return to? What feels overdesigned, and what feels just right? Make choices about your preferences—and, more important, understand why you prefer them. Ask yourself what values those preferences express. Minimalism? Opulence? Precision? Warmth?

The third step is reflection. Taste is not static. As you evolve, so will your sensibilities. Keep track of how your preferences change. Revisit things you once loved. Reconsider things you once dismissed. This is how taste matures—from reaction to reflection, from preference to philosophy.

👀 Last week, I made Patrick watch Goodbye, Dragon Inn with me. It's an incredible (and incredibly slow) film that explores nostalgia in unsettling ways: a decrepit theatre, a motley crew of strangers watching an old film for the very last time, extremely slow single takes, including one several-minutes-long static shot that will make you squirm in your chair.